Market downturns and recessions may seem easy to predict. But timing the market is extremely difficult without the benefit of hindsight.

Ultimately, fundamentals drive stock performance. Over shorter periods of time, this relationship is not very reliable, as stock prices are also affected by a tremendous amount of market noise—announcements from the Fed, political angst or exuberance, fears of war, hope of peace, and a host of other factors. But in the end, a company’s market value is determined by its potential for future growth and profitability.

In the equity strategies that our firm manages, we focus on fundamental research of individual companies to assess their long-term prospects, and we avoid making decisions that require guessing about short-term market movements. When clients ask us about timing the market (for example, about potentially exiting the market to avoid a market correction) there is almost no situation in which we would recommend doing so. As we will discuss in this article, one needs to be highly precise about two market-timing decisions—when to exit, and when to re-enter—in order to truly benefit. In our experience, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to do so effectively.

Even if investors discard the notion of broadly timing the market, they still may have questions about staying invested in actively managed strategies during what they perceive as a risky market. Are there any signals amidst the noise that can offer them comfort? Well, we believe that broader economic fundamentals are important for long-term stock valuations. These fundamentals determine the overall environment in which corporations operate. While one can’t predict a recession with any more accuracy than a market correction, we have learned two things from the last 50 years of market history: Market corrections were mild unless they coincided with a recession; and, active managers generated meaningful alpha during recessionary periods. These facts suggest that if the economy and markets do turn sour and we experience a major market correction, actively managed strategies may in fact weather the storm better than indexes if they focus on robust, healthy businesses.

The Folly of Market Timing

At the risk of stating the obvious, it would be great if we could time market corrections! Get out of the market when it peaks, get back in when it bottoms out, preserve your capital—that is an ideal scenario. The problem is that it is impossible to time market corrections effectively, at least in our experience.

We think about the market and individual stocks in shades of gray, not in black and white. We develop a likely range of upside and downside scenarios over a period of years, and try to make decisions that position us relatively well across all of those scenarios. However, trying to avoid a market correction is a very different exercise. It involves two very distinct and momentous decisions—when do you exit, and when do you re-enter? According to history, you are unlikely to get much benefit from a market-timing attempt unless you are highly accurate about both of those decisions.

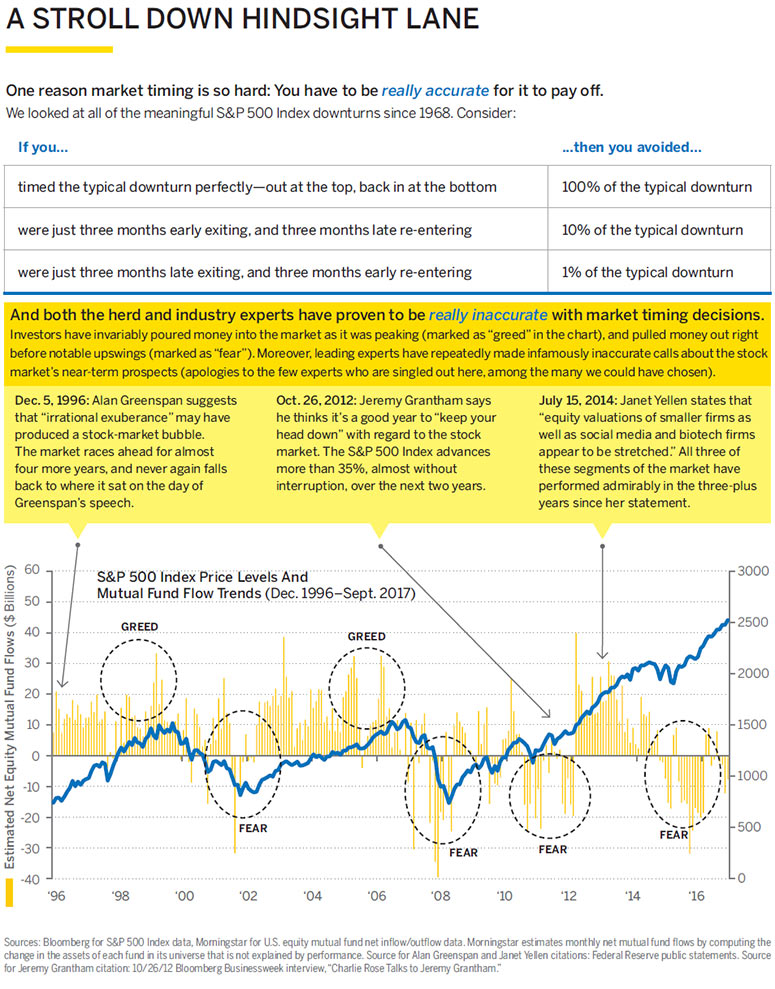

We looked at all of the market corrections in the S&P 500 Index from 1968 to the present, and calculated how well an investor would have fared by exiting the market at various points before and after the market’s peaks, and then re-entering the market at various points before and after its troughs. We found that unless investors timed it perfectly on both ends—or at minimum, timed at least one of the decisions perfectly—in most cases they would still bear the brunt of the losses from the downturn. Just being three months off for each decision meant that investors on average would have experienced 90% or more of the average downturn (see chart "A Stroll Down Hindsight Lane" below), and in many cases would have missed out on positive returns.

If you see this data as a challenge to simply “do better” at market timing, be forewarned: The broad investing herd and noted financial experts have repeatedly tried—and repeatedly failed—to time the market. The chart below also shows how the investing public has invariably entered and exited the market at the worst possible times (as measured by monthly net equity mutual fund flows); additionally, otherwise brilliant economists and market experts often put a stake in the ground regarding the market’s future path, only to be proven sorely mistaken. Finally, note that taxes and transaction costs are additional hurdles that market timers must overcome.

It's the Economy

In short, precise market timing is impossible, in our view. However, we still want to be attuned to information that can help us understand the probability of a downturn. Additionally, we are always looking for data that may offer clues about the potential length and severity of the next downturn.

One factor that seems to be quite relevant is the health of the economy when a downturn occurs. Specifically, we know from history that downturns tend to be longer and more severe if they occur during an economic recession, and milder and shorter in the absence of a recession. This is obviously relevant when we consider our clients’ overall exposure to risk assets, and it is also important for our equity research analysts and portfolio managers as they think about the prospects of the individual stocks in their portfolios.

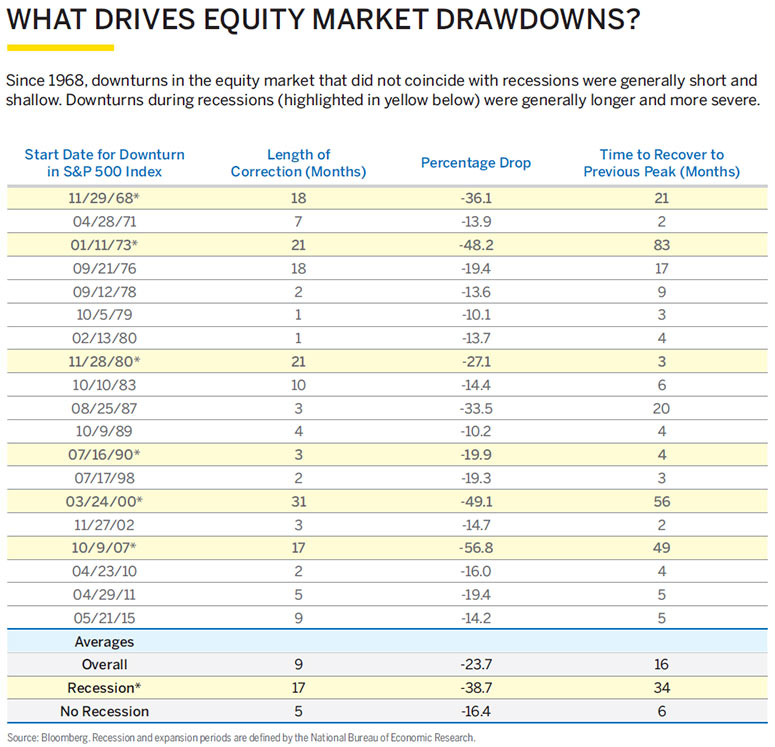

The table below offers a glimpse of each of the notable S&P 500 Index downturns from 1968 to the present. Downturns that overlapped recessions are highlighted in yellow.

The average downturn during recessionary periods lasted 17 months, resulted in a 38% drop in market value, and required a 34-month period before the Index recovered to its prior peak. The average downturn in non-recessionary periods lasted only five months, resulted in a 16% drop in value, and required only six months of recovery time before the Index bounced back. Recessions appear to play a notable role in both the length and severity of downturns.

As we mentioned earlier, we don’t believe that it’s any easier to predict a recession than it is to predict a market correction, and we don’t build plans or base decisions on predictions about either. But there has been an undeniable relationship between recessions and the severity of downturns over time, so we can at least use that knowledge as a filter to assess the potential significance of incoming data that might affect the economy.

The Value of Active Management

As we proceed further in this series, we will move into discussions that focus more on individual stock selection, and on the value that active management can produce for investors—particularly during periods when the stock market or the economy is potentially poised for a reversal. To close this article, we offer some introductory evidence to support the notion that managers tend to earn their stripes during periods of economic weakness.

As we proceed further in this series, we will move into discussions that focus more on individual stock selection, and on the value that active management can produce for investors—particularly during periods when the stock market or the economy is potentially poised for a reversal. To close this article, we offer some introductory evidence to support the notion that managers tend to earn their stripes during periods of economic weakness.

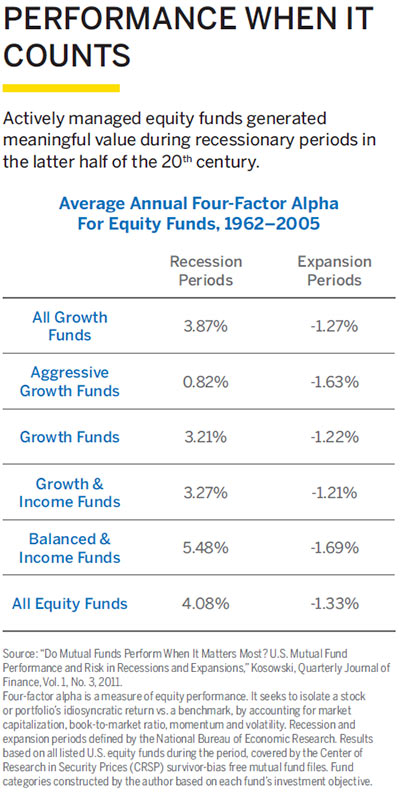

The table at right summarizes the results of a 2011 study by Robert Kosowski, who found that managers indeed tended to struggle during economic expansions but produced meaningful value during recessionary periods.

This data makes sense intuitively. During periods when the economy is strong and the market is running, people tend to be more confident and more willing to speculate on riskier companies.

Additionally, the ongoing popularization of passive investing may be contributing to a lack of selectivity in markets. Index funds essentially ignore the intrinsic value or current price of any given stock, and as capital shifts to index funds, those funds may provide support for all stocks.

But when the economy weakens, when broad-market confidence fades—that is when we believe it is most important to be selective about the companies we choose to own. As we said at the start of this article, fundamentals ultimately drive stock performance. In the absence of other exogenous factors to buoy a company’s stock price, the only thing left is that company’s foundation—the health of its balance sheet, the strength of its business model, and its ability to generate earnings and cash flow.

The views expressed are those of the author and Brown Advisory as of the date referenced and are subject to change at any time based on market or other conditions. These views are not intended to be and should not be relied upon as investment advice and are not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance and you may not get back the amount invested.

The information provided in this material is not intended to be and should not be considered to be a recommendation or suggestion to engage in or refrain from a particular course of action or to make or hold a particular investment or pursue a particular investment strategy, including whether or not to buy, sell, or hold any of the securities or asset classes mentioned. It should not be assumed that investments in such securities or asset classes have been or will be profitable. To the extent specific securities are mentioned, they have been selected by the author on an objective basis to illustrate views expressed in the commentary and do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for advisory clients. The information contained herein has been prepared from sources believed reliable but is not guaranteed by us as to its timeliness or accuracy, and is not a complete summary or statement of all available data. This piece is intended solely for our clients and prospective clients, is for informational purposes only, and is not individually tailored for or directed to any particular client or prospective client. Private investments mentioned in this article may only be available for qualified purchasers and accredited investors. All charts, economic and market forecasts presented herein are for illustrative purposes only. Note that this data does not represent any Brown Advisory investment offerings.

The S&P 500® Index represents the large-cap segment of the U.S. equity markets and consists of approximately 500 leading companies in leading industries of the U.S. economy. Criteria evaluated include market capitalization, financial viability, liquidity, public float, sector representation and corporate structure. An index constituent must also be considered a U.S. company. Standard & Poor’s, S&P, and S&P 500 are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC (“S&P”), a subsidiary of S&P Global Inc.