Beutel Goodman US Large-Cap Value - Standard RFP

File Uploaded Date

INTL - U.S. Large-Cap Growth Strategy - Standard RFP

File Uploaded Date

2024 Asset Allocation Perspectives / Outlook

INNOVATION IN AI AND GLP-1 MARKETS

HIGHLIGHTS

Technology innovation has provided a near-constant boost to economic productivity, especially over the past 100-150 years. Since 1860, lifespans have roughly doubled in the U.S., while economic productivity (GDP per capita) has grown elevenfold during that period (even after adjusting for inflation!).

We are in the early stages of two potential “gamechanger” innovations right now—generative AI, and GLP-1 drug treatments for obesity. We have sought to establish investment exposure in both markets, in such a way that we can participate in upside without taking on the binary risk of more speculative opportunities.

Nothing captures the attention of investors like the promise of a new technology. Companies at the forefront of technology can rapidly take over markets and/or invent entirely new industries, while laggards and those directly threatened by disruption can find themselves wiped out more quickly than they ever could have imagined.

Over the past year, equity markets were heavily influenced by technology innovation—specifically, the emergence of generative AI technology and the rise of glucagon-like peptide drugs (GLP-1s)—and we are just starting to see the impacts play out across various sectors of the market.

Generative AI

The launch of ChatGPT in late 2022 opened a floodgate of investor interest in generative AI. From an investment perspective, NVIDIA has thus far been deemed the winner of the early rounds of AI innovation; its shares appreciated by 239% in 2023, on the heels of heavy demand for its GPUs by customers seeking to train AI applications. But the big challenge for investors is to figure out where value will accrue within the AI tech stack going forward: Hardware or software? Learning model or application?

One can think about the opportunity and impact of AI across four broad categories:

- End-user applications: Companies like Adobe, Wolters Kluwer and Intuit offer applications directly to consumers or businesses that could benefit enormously from embedded AI (and in some cases, they already are).

- Foundation models, including large language models (LLMs): This includes the development and deployment of advanced AI models, including large language models such as ChatGPT, as well as proprietary or use-specific datasets such as those owned by London Stock Exchange Group.

- Cloud compute: Major cloud service providers like Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services (AWS), and Google Cloud play a significant role in AI infrastructure.

- Technical infrastructure: This category covers GPUs, networking, memory and related value chains, including semiconductor equipment. Constituents include companies such as Marvell Technology, Taiwan Semiconductor, ASML and NVIDIA.

These four groups face fairly different opportunities and risks. Currently, we are most enthusiastic about the technical infrastructure and cloud computing opportunities. NVIDIA has been a clear winner so far, and currently its GPUs are best-in-breed solutions for anyone seeking to run AI applications and infrastructure. Taiwan Semiconductor and ASML represent the “picks and shovels” that NVIDIA relies on to manufacture those GPUs. Training and running AI models will require high-powered hardware for the foreseeable future, which should be a boon to cutting-edge semiconductor companies. Within cloud compute, Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon have demonstrated that scale and resources matter in AI. The three tech behemoths are pouring resources into their respective cloud infrastructures, all to support additional AI workloads. Our investments across both of these hardware-centric categories added meaningfully to performance in 2023.

Moving up the tech stack, we expect competition to be fierce among AI foundation models—the core engines that drive AI-powered applications. Our research team has noted that these models are becoming easier to create and scale and thus face the risk of becoming commoditized going forward. OpenAI’s GPT-4 LLM, which powers ChatGPT, has so far captured the most mindshare among consumers and developers, but developers can build applications on other competing models, such as LLaMa (Meta’s open-source LLM), Gemini (Alphabet’s latest LLM) or Claude2 (developed by Anthropic, a private company and competitor to OpenAI that has recently received investments from Alphabet and Amazon).

Finally, application software companies like Intuit or Adobe may have current advantages, but they will likely need to be proactive about infusing AI into their applications to stay ahead of competitors. Throughout 2023, we saw software-as-a-service (SaaS) companies taking steps to add AI functionality; for example, Intuit incorporated a new AI Assist platform across its personal finance solutions. Of course, companies will need to invest more resources into these products, which may impact margins if customers aren’t willing to pay extra for new features. We expect more companies to announce new AI-enabled products, but given a more constrained economic environment, we also expect investors to put a premium on situations where AI truly leads to better customer outcomes.

In these early innings of AI, we’ve benefited from both public and private AI-related investments:

- Public markets: Our investments in cloud computing and technical infrastructure have already produced strong results, and we believe that companies like NVIDIA, Microsoft and Alphabet have the resources and scale to maintain their competitive positioning. Key questions going forward: How long will we see such elevated demand for these products (especially for NVIDIA’s GPUs)? Further, will margins be squeezed in the future, by price competition or “cap ex competition” among the key industry players?

- Private markets: Private market volumes and valuations are down broadly, but activity tied to AI has been robust. One recent example is Hugging Face, an AI company that recently raised $235 million in a series D financing round, at a post-money valuation of $4.5 billion according to Pitchbook— nearly 100x recurring revenue. Several of our private fund managers hold attractive stakes in promising AI companies, which should be a boon going forward, but we note that it may be more challenging to find good value in the space now, given the recent runup in AI-related valuations.

Everything discussed above about AI technology is mostly focused on the intermediate term—how AI investments might pay off over the next five-to-seven years. Over the long term, the key question investors should consider in the coming years is how AI will change the world—and specifically, whether it will radically change productivity in the way that major technology advancements have in the past (see chart below). Global growth faces several challenges, from an aging populations to heavy sovereign debt to geopolitical disruptions, but AI and its promise of significant productivity gains could offset some of these headwinds.

TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES AND THEIR IMPACT ON PRODUCTIVITY AND GENERAL WELFARE (1860–2023)

Throughout history, technological innovations have tended to be powerful drivers of productivity (measured in this chart by the U.S. GDP per capita statistic over time) and general welfare (measured here by average U.S. life expectancy). The dot plot diverges far above the trendline during multiple historical periods marked by the advent of major transportation, communication, healthcare and other achievements. (Note that productivity gains are shown on a logarithmic scale.) Each dot on the chart below denotes a calendar year spanning from 1860-2023.

Source: Gap Minder, as of 12/31/2023.

GLP-1s

In 2023, the “glucagon-like peptide” (“GLP-1”) drug market exploded. For several sleepy decades, these drugs were used to treat diabetes, but newer GLP-1s can now successfully treat obesity and lower the risk of heart disease. Growth so far has happened outside of insurance reimbursement, and if insurers are eventually persuaded to cover these drugs for obesity, it would expand the market greatly (the drugs currently cost patients about $1,000 per month out of pocket).

GLP-1 leaders Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly were among the best-performing healthcare names of 2023, on expectations about the future earnings impact of their respective drugs. Conversely, the market punished those potentially threatened over the long term by these emerging GLP-1 options, such as Intuitive Surgical and Edwards Lifesciences (GLP-1s may reduce overall demand for heart surgery), Dexcom and Insulet (GLP-1s may prevent many cases of diabetes in the future) and ResMed (maker of CPAP machines for sleep apnea).

These drugs have led many to speculate more broadly about a future where obesity is meaningfully reduced, and how other sectors of the economy and society may be affected. Here are a few of the many potential shifts we are considering:

- Orthopedics: A less obese population would likely exhibit different patterns of injury over time, forcing the health care industry to adapt. Populations may require fewer joint replacements if carrying less weight; on the other hand, people may become much more active, which could drastically increase the incidence of sports injuries and sports-related surgeries.

- Clothing/retail: A GLP-1 saturated world may produce hundreds of thousands of consumers every year who need to purchase an entire new wardrobe of clothing; in the current economic cycle, that could reaccelerate growth for some apparel companies.

- Online dating: If a few million people in the U.S. lose a ton of weight over the next year, it seems fairly likely that many of those people would feel newly confident and better prepared for the dating scene.

- Airlines: Fuel accounts for nearly a quarter of airline operating expenses; given the thin margins at which airlines operate, even a small reduction in passenger weight could translate into a significant boost to profitability.

- Restaurants and snack foods: To what extent will mass adoption of GLP-1s reduce demand for snack foods? To what extent will the “high calorie, high price” model followed by so many casual restaurants need to change in the future?

Market size is a key question in measuring the potential impact of GLP-1s. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, as of Dec. 31, 2023, roughly 200 million U.S. adults are overweight, obese, or morbidly obese. What is the “steady state” market for GLP-1s—50 million of those adults? 10 million? All 200 million? The answer will determine how all of the aforementioned industries are impacted, but it will take time for our teams and other investors and analysts to get a better sense of the market’s scale.

Note: All commentary sourced from Brown Advisory as of 12/31/23 unless otherwise noted. Alternative Investments may be available for Qualified Purchasers or Accredited Investors only. Click here for important disclosures, and for a complete list of terms and definitions.

2024 Asset Allocation Perspectives / Outlook

U.S. FISCAL SITUATION

HIGHLIGHTS

Throughout history, many nations and empires have met their end when they overextended financially, so it is no surprise that sovereign debt has been a key political issue in the U.S. since its founding.

The U.S. responses to the 2008-09 credit crisis, and later the pandemic, required massive fiscal stimulus, such that the U.S.’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen to levels not seen since WWII.

Investors should monitor several factors—the absolute level of debt, the cost of servicing that debt and the trajectory of debt levels—to assess when (or if) these concerns might begin to influence market returns.

The national debt and the size of the deficit have been a political issue since the Constitution was ratified in 1789. Ronald Reagan famously visualized the debt as a stack of $1,000 bills stacked 67 miles high (when the national debt first passed $1 trillion), and Ross Perot made it the centerpiece of his prominent third-party presidential campaign in 1992.

Attention to “debt politics” has been renewed of late, on the heels of the most significant peacetime expansion of government debt in U.S. history. The U.S. countered two major economic disruptions during this period—the 2008-09 credit crisis and the pandemic—with massive fiscal stimulus to stave off dire economic consequences. The plans in both cases “worked,” but today, the U.S. faces a 120% debt-to-GDP ratio, up from 63% in 2007. Until recently, low interest rates and cheap debt allowed the government to largely ignore this problem, but with Treasury yields soaring over the last two years, the Fed is feeling as much of a pinch from higher rates as every other American household.

The problem stems from three factors: the size of the debt, the rising cost of debt service, and the trajectory of deficit spending. None of these are truly at unprecedented levels, but the combination creates a challenging fiscal picture.

Level of debt: While the “official” level of U.S. public debt is around $32 trillion, the relevant figure is its “net debt” of $26 trillion (this figure excludes loans between Federal entities). This figure is roughly 95% of GDP today (it peaked at 105% just after WWII), as shown in the chart below. This ranks the U.S. in the middle of the G-7 pack (see chart below); Italy and Japan’s comparable ratio has exceeded 100% for decades, and the U.K. peaked at 250% after WWII, so the current scale of U.S. debt does not represent an inevitable crisis.

VOLUME VS. EFFICIENCY

Despite its large absolute debt balances (both net and total), the U.S. is not overly indebted in relation to other developed countries. The relative indebtedness of the U.S. as a percentage of GDP places the U.S. in the middle of the developed-economy pack.

Source: Bloomberg, Brown Advisory analysis.

Cost of debt: Despite the aforementioned growth in debt levels, U.S. debt service in 2021 was only 1.5% of GDP, below its post-WWII average, all thanks to low interest rates. However, rising rates have changed all of that for the world’s largest lender. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the government’s net interest expense was $640 billion in 2023, and that this figure has grown by 35% in each of the past two years. It will almost surely continue to grow as the government refinances maturing debt at higher rates; the CBO expects net interest expense to exceed $1 trillion by 2029, and represent 3.2% of GDP, the highest rate on record. The chart below illustrates the extent to which interest payments are growing in the U.S. as a percentage of government receipts, a pattern we are not seeing in other developed economies.

Further, higher debt service costs create pressure to expand deficit spending (see chart below), which complicates any effort to reduce the size of the debt.

Deficit trajectory: The U.S. budget deficit ballooned to 15% of GDP in 2020 as the government rallied to support a locked-down country; the situation improved markedly in the following years, dropping to around 5% of GDP in 2022—still above the post-WWII average of 2%–3% but seemingly on the right track.

But in 2023, tax receipts fell, spending grew, and the deficit jumped up above 6% of GDP again. Worse, the current deficit trajectory appears structural, as opposed to event driven. During the post-WWII era, deficit spending was required by the moment, and after the war ended, both the U.S. and U.K. governments produced budget surpluses for the next decade. But spending today is different; Social Security and Medicare cost the U.S. $2 trillion in 2022, and given the aging demography of the U.S., these programs’ costs are very likely to grow faster than GDP without meaningful reform. Further, interest costs on the debt are likely to grow meaningfully; overall, the scale of interest costs and entitlement spending makes overall spending that much more difficult to curtail and puts ever-greater pressure on other parts of the budget.

In sum, the combination of debt scale, debt cost and deficit trajectory may not produce an imminent crisis, but it suggests that a crisis is inevitable if these factors aren’t managed more effectively going forward.

Addressing the Elephant in the Room

The consequences of excessive debt cannot be avoided forever. Even if there is no storm on the immediate horizon, the U.S. economy is already paying a burden for the government’s debt, in the form of cash outflows to international holders of Treasury bonds, the potential dampening of private investment activity if the government’s borrowing is sopping up too much market demand from investors, and finally in the form of higher interest rates (which are boosted by the government’s insatiable appetite for capital). Overall, high debt levels can create a challenging feedback loop where low economic growth leads to weak government receipts (from income taxes and such), which leads to higher deficits and yet more debt, which further increases pressure on economic growth. Italy and Japan have been trapped in such feedback loops for decades; the U.S. needs to address the situation before something similar happens to it.

There are three primary ways for countries to trim debt:

- Economic growth: The most “pleasant” path to reducing debt levels is to “grow beyond them.” The last time the U.S.’s debt-to-GDP ratio fell notably was in the 1990s, when the tech boom and dot-com rush ushered in multiple years of high tax receipts, budget surpluses and a rapidly growing GDP in relation to debt. The challenge is that “rapid economic growth” is not a policy option; governments can try to facilitate growth, but in the end, game-changing growth cycles emerge from innovation and ideas, not from policy tweaks.

- Austerity: European policymakers imposed this belt-tightening strategy on highly indebted countries like Greece and Italy (to various extents) when dealing with Europe’s debt crisis a decade ago. While fairly straightforward in addressing the issue, this solution is politically unattractive to most policymakers; the backdrop of the 2008-09 credit crisis empowered this approach from the EU, but in many “normal” situations, austerity would nearly ensure defeat in the next election. Austerity also must be balanced with economic considerations, as it generally produces a drag on economic growth.

- Inflation: This path is the equivalent of writing down one’s debt valuation; since government debt is in nominal dollars (aside from TIPS), inflation would reduce the effective debt load relative to future GDP totals. In theory, an inflation rate of 3%–4% would stoke at least nominal GDP growth, which would have many of the same benefits discussed under economic growth.

Historically, governments have turned to this option, but coordinating monetary and fiscal policy to this end can ruin the public’s confidence in a central bank, and playing with inflation is akin to playing with economic fire (Argentina and Turkey are good recent cautionary tales, with inflation exceeding 100% in both countries for a time).

None of these three “solutions” are straightforward to execute, but as the debt rises higher, the need for dramatic action rises as well. The market may eventually force policymakers to take swift action, which can be very painful—unfortunately, governments rarely take painful proactive steps in these situations. The Eurozone crisis of 2011 is a great example; Italy’s debt situation hadn’t changed meaningfully in many years, but in 2011, a scare around Eurozone government debts, centered on Greece, led to a spike in Italian government bond yields. Seemingly overnight, the market was demanding structural change in Italy before funding new bonds, so the government had to raise taxes and reduce spending at a time when its economy was floundering. We believe the U.S. should act now to avoid pain later, but the current state of congressional politics does not offer much hope for meaningful action—especially when there is no immediate crisis to force Congress to act.

Unchecked debt levels will inevitably put pressure on interest rates, economic growth and, ultimately, on returns generated by financial markets. That impact is hard to see or feel; it is usually overwhelmed on a year-to-year basis by cyclical factors, but it is always there, nonetheless. Debt and deficit issues in the U.S. have contributed to our broadly cautious long-term outlook for equity returns and have influenced our decision to be more conservatively positioned in today’s environment.

Note: All commentary sourced from Brown Advisory as of 12/31/23 unless otherwise noted. Alternative Investments may be available for Qualified Purchasers or Accredited Investors only. Click here for important disclosures, and for a complete list of terms and definitions.

2024 Asset Allocation Perspectives / Outlook

STATE OF THE U.S. CONSUMER

HIGHLIGHTS

The pandemic and its related economic consequences have had a meaningful impact on the trajectory of financial health for U.S. consumers.

During the pandemic, Americans saved more and benefited from low rates while they lasted. But high rates, inflation, and the resumption of student loan payments have largely reversed those trends, leading to broad concerns about the health of consumer balance sheets.

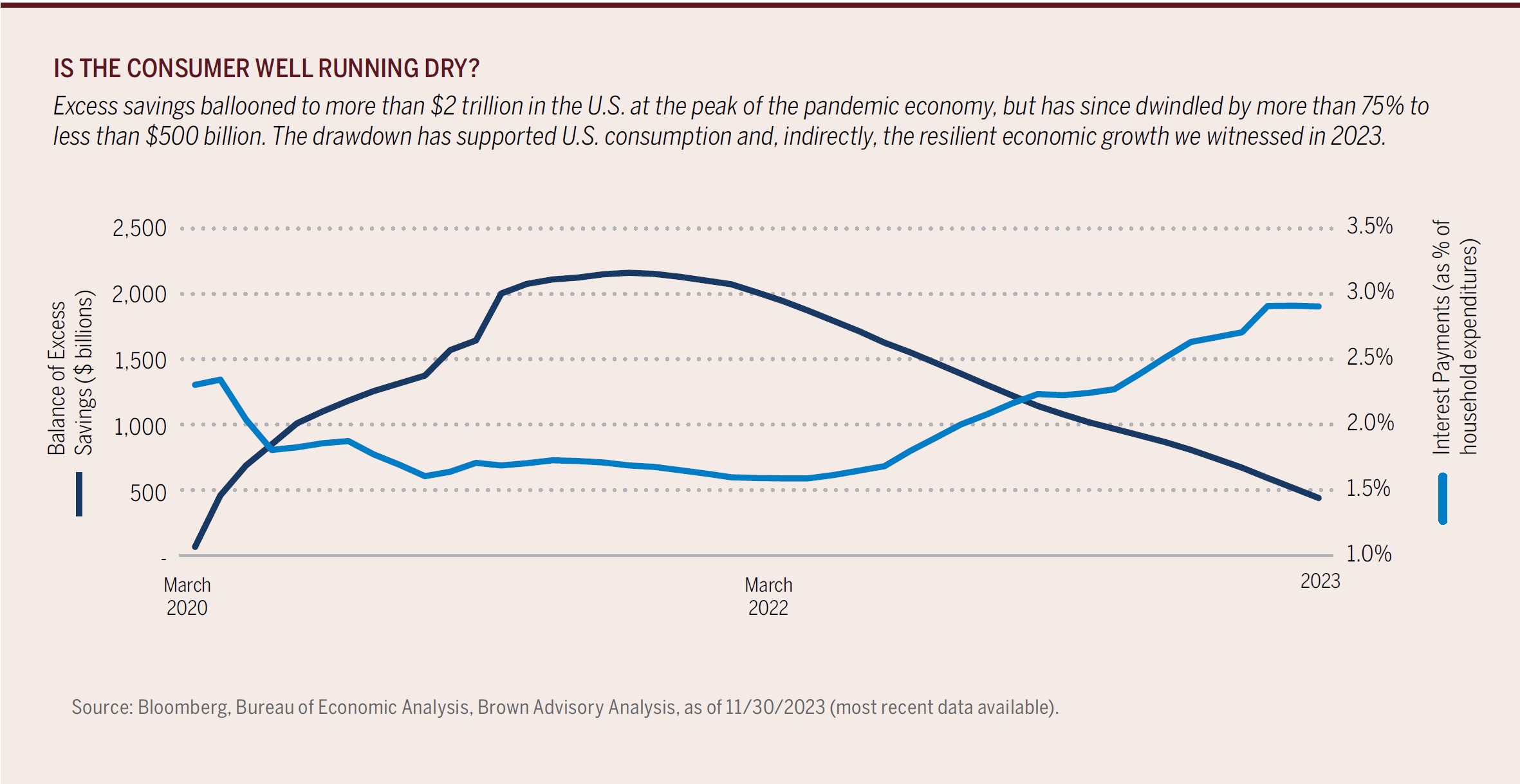

U.S. Consumer spending has been the foundation of post-pandemic economic growth and contributed to the economy’s surprising resilience in 2023. Household spending drives more than 60% of U.S. GDP, and nearly four years after COVID-19 appeared, that spending isn’t letting up. Pandemic stimulus and lockdowns boosted the personal savings rate to 33% in 2020 and raised excess savings to a peak of $2.1 trillion; the purchasing power of households soared following these temporary incentives, partly mitigating the impact of higher interest rates. At the start of 2024, unemployment was historically low, wage growth was outpacing inflation, jobs were being added at twice the 100,000 monthly gains needed to keep the economy growing, and job openings still exceeded unemployed workers by a healthy margin.

Consumer staples stocks missed this wave and performed poorly relative to other S&P 500® Index sectors in 2023. Investors tend to view this dividend-heavy sector as a bond proxy, and as short-term yields rose to 5%, there was a rotation out of these rate-sensitive stocks into higher-yielding and risk-free U.S. Treasuries. On the other hand, consumer discretionary stocks performed quite well; traditionally, this sector performs well early in a cycle of economic improvement (and sector performance benefited greatly from the fact that Amazon and Tesla are both considered consumer companies in the Index).

When one throws in the increase in net worth for many consumers (thanks to rising equity valuations and real estate prices), the overall picture for U.S. consumers has been extremely healthy. However, headwinds are emerging; the typical consumer is now draining their pandemic savings with the resumption of student loan payments, higher mortgage and credit card rates, and higher prices across the board.

Depletion of excess savings: Excess savings in the U.S. fell from $2.1 trillion to $500 billion as the economy normalized from March 2020 through November 2023 (see chart below).

Higher rates: Rising mortgage rates are starting to take their toll on consumer confidence. Approximately 82% of outstanding U.S. mortgage debt is still financed at rates below 5%, but new 30-year loans are charging 7%, greatly dampening activity in consumer real estate as buyers and builders alike are deterred by higher rates.

Auto and credit card debt is also being impacted. Average credit card rates have climbed to 24%, and some measures of delinquency rates are at their highest level since 2012. According to TransUnion, average consumer use of available credit on their cards is in line with pre-pandemic levels but rising. We also note the somewhat shocking rise of “buy now, pay later” (BNPL) transactions—BNPL volumes grew 50% in 2023 vs. 2022. We are monitoring this development, given the very high interest rates at times for BNPL loans (PayPal’s solution charged a 35% interest rate at time of publication) and the ability for consumers to “loan stack” as they take loans from multiple stores.

Resumption of payments: Student loan payments in the U.S. resumed in October 2023 after a three-year break during and after the pandemic. This is a massive consumer debt category, representing about 1% of annual consumer spending; about 17% of consumers have student loan debt. Although a small impact overall, this is a greater headwind for middle-income consumers (and relevant consumer categories).

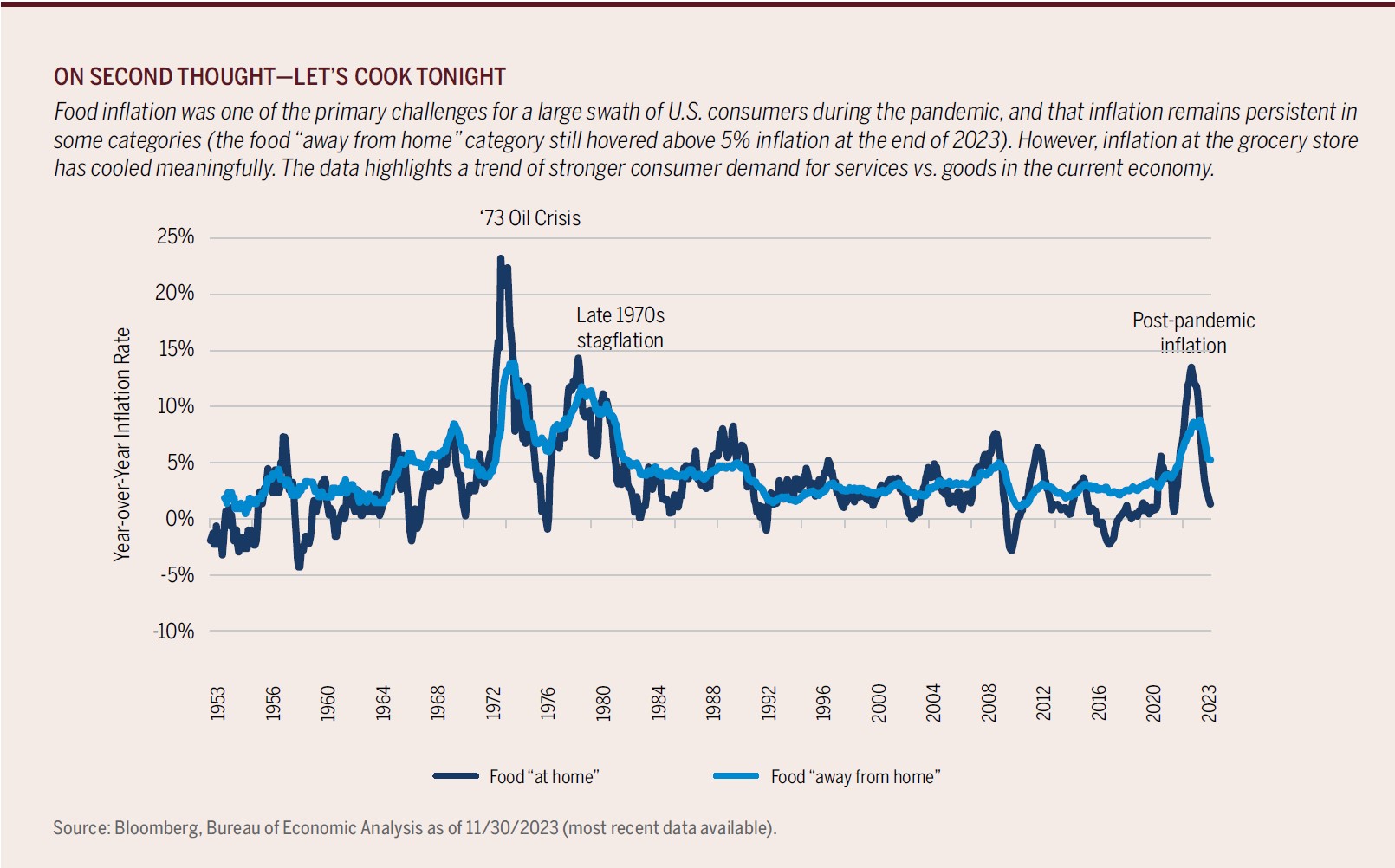

Inflation: Lastly, inflation remains elevated in essential categories such as housing and food “away from home” (see chart above), a fact that may dampen discretionary spending in other categories. A welcome exception has been gasoline prices, which have come down notably from their 2022 peak levels. Food “at home” prices cooled down in 2023, providing some relief to household budgets.

Shifting Spending Patterns

As the economy has transitioned from its “pandemic footing” to become more normalized, consumer behavior has unsurprisingly been in flux. We moved through a period of “revenge spending” on discretionary items by consumers angry about their lives being constrained, and, more recently, we are seeing consumers trade some of this spending on goods, in favor of spending on experiences such as restaurants, travel and leisure (Royal Caribbean and DraftKings each had terrific years in 2023). Meanwhile, consumers are increasingly opting for cheaper, “private label” products in essential categories (staple foods, cleaning supplies, etc.) as they choose price over brand loyalty. Private label products have also improved greatly in recent years, making them more competitive with established brands that can carry prices from 15% to 30% higher.

Bottom Line on the Consumer

Higher interest rates and inflation historically temper consumer spending, but the impact has been less significant during this cycle. Consumers remain confident about their employment, still have some excess savings, and are willing to spend large portions of their income. Mortgages, which make up 70% of consumer debt, are locked in at low interest rates, even as other forms of debt have seen rates adjust more quickly.

But warning signs are appearing, such as those mentioned above. Interest payments are rising as a percentage of personal income; further, personal savings rates have largely reverted to pre-pandemic levels—slightly lower in the U.S., slightly higher in the U.K. and Canada (see chart below). In 2024, we expect softer consumer spending and disposable income growth, and further expect that lower-income households will feel the greatest pinch from inflation and higher rates.

Note: All commentary sourced from Brown Advisory as of 12/31/23 unless otherwise noted. Alternative Investments may be available for Qualified Purchasers or Accredited Investors only. Click here for important disclosures, and for a complete list of terms and definitions.

2024 Asset Allocation Perspectives / Outlook

2024 ASSET ALLOCATION VIEWS

Discussion of 2024-2026 Scenario Analysis

Asset Allocation Scenario Analysis

Our asset allocation stance is largely based on our long-term return and drawdown risk estimates across asset classes. For equities, the key inputs for our long-term return estimates are starting valuations, economic growth expectations (or potential GDP growth) and changes in interest rates. For fixed income, the key input is starting yields (incorporating both base government bond yields and credit spreads), with some influence from the slope of the yield curve and anticipated changes in yields.

The year 2023 brought another tangible increase in bond yields (despite the major decline at the end of the year), and equity market valuations rose broadly during the year—both of these trends reduced the overall long-term appeal of equities vs. bonds. Therefore, we have been utilizing fixed income and credit more extensively than we did when interest rates were far lower.

Equity markets are also generating diverse return streams, by market segment as well as by individual company. Small caps have lagged large caps for some time (small caps tend to be sensitive to interest-rate changes), so our forward view of small caps is more optimistic than that of large caps (which are more fully valued at the moment). We have a similar view about the runway available in emerging markets vs. developed markets. Of course, small-cap and emerging-market investments tend to be more volatile and more cyclical, especially during uncertain times, and we must take this into account with any allocations to those asset classes.

Medium-Term Outlook (18 to 36 Months)

Most major economies fared better than expected while combating inflation and rising rates in 2023. With inflation starting to ease, hopes have risen that central banks may be able to ease interest rates and avoid a recession.

The odds of a soft landing have increased over the past year, but the global economy is far from out of the woods, and most major economies have already slowed to some extent. The full pressure of higher interest rates has yet to be felt; that pressure will mount as old, lower-cost debt is replaced at higher coupons. Geopolitical tensions and weakness across U.S. regional banks are additional threats.

The European and Chinese economies are at risk from several broad factors, including demographic challenges that are already weighing on growth. China’s ongoing real estate and debt situation is also a meaningful concern for investors.

With so much uncertainty, it is more important than ever to prepare our clients’ portfolios for a wide range of scenarios. A good deal of our thinking this year, and last year, has been focused on the interplay between interest rates and inflation, and how those factors will affect the broader economy. How central banks “land” the economy will depend on their aim: how well they estimate the “true neutral” policy rate—in other words, an interest-rate equilibrium point that neither restricts nor stimulates the economy. It is an important balancing act: Recession looms if they err on one side, while renewed and stubborn inflation awaits them if they err in the other direction. We consistently labor to ensure that our clients are as well prepared as possible for this full range of potential market outcomes.

Note: All commentary sourced from Brown Advisory as of 12/31/23 unless otherwise noted. Alternative Investments may be available for Qualified Purchasers or Accredited Investors only. Click here for important disclosures, and for a complete list of terms and definitions.

2024 Asset Allocation Perspectives / Outlook

2024 ASSET ALLOCATION VIEWS

Baseline Allocation Model and Long-Term Projections By Asset Class

For many years, we have used a consistent process for communicating and adjusting a baseline asset allocation strategy for portfolio managers to use with clients. The approach involves the creation of a “standard model” (we tend to avoid terms like “standard” or “model” because our client portfolios are highly customized and rarely adhere strictly to any sort of model), based largely on our long-term conviction about each major asset class, and then periodic “tweaking” as needed to capitalize on an undervalued asset class or to trim exposure to an asset class with elevated risk.

The long-term ranges in the tables below and at left express what we consider to be prudent boundaries for each asset class in a typical, long-term-oriented portfolio, given our 10-year outlook for that asset class. (For example, we currently feel that U.S. equities merit an allocation of 25-35% of a typical client’s portfolio.) Key drivers of our thinking are our expectations for baseline 10-year annualized return, maximum likely drawdown risk (expressed as worst likely one-year outcomes over 10-year and 20-year periods) and the alpha opportunity we think we can reasonably achieve from selection of adept managers. We provide these expectations in the tables.

The medium-term targets in the tables express our current guideline for where to position portfolios within each asset class. Intermediate-term adjustments are, appropriately, based on a disciplined look at various intermediate-term market scenarios that may play out in the next two to three years (these scenarios are discussed further in the next section).

The hypothetical performance depicted in the chart above represents the long-term return estimates. Estimates are calculated using starting valuations and estimates of long-term earnings growth potential and starting level of interest rates. Alpha opportunity is an estimated range measured from an analysis of active managers across each asset class and the hypothetical potential alpha one could achieve through manager selection. Drawdown risk is based on beta-adjusted historical drawdowns of each asset class. The data above is not intended to be a representation of expected returns and should not be relied on in this context. Further information on performance calculations as well as the risks and limitations of investing based on hypothetical returns is available upon request.

The hypothetical performance depicted in the chart above represents the long-term return estimates. Estimates are calculated using starting valuations and estimates of long-term earnings growth potential and starting level of interest rates. Alpha opportunity is an estimated range measured from an analysis of active managers across each asset class and the hypothetical potential alpha one could achieve through manager selection. Drawdown risk is based on beta-adjusted historical drawdowns of each asset class. The data above is not intended to be a representation of expected returns and should not be relied on in this context. Further information on performance calculations as well as the risks and limitations of investing based on hypothetical returns is available upon request.

The hypothetical performance depicted in the chart above represents the long-term return estimates. Estimates are calculated using starting valuations and estimates of long-term earnings growth potential and starting level of interest rates. Alpha opportunity is an estimated range measured from an analysis of active managers across each asset class and the hypothetical potential alpha one could achieve through manager selection. Drawdown risk is based on beta-adjusted historical drawdowns of each asset class. The data above is not intended to be a representation of expected returns and should not be relied on in this context. Further information on performance calculations as well as the risks and limitations of investing based on hypothetical returns is available upon request.

Note: All commentary sourced from Brown Advisory as of 12/31/23 unless otherwise noted. Alternative Investments may be available for Qualified Purchasers or Accredited Investors only. Click here for important disclosures, and for a complete list of terms and definitions.

2024 Asset Allocation Perspectives / Outlook

OUR CURRENT STANCE

Investors are welcoming a new era where they can pursue target returns without taking on undue illiquidity or complexity. Given higher interest rates, returns from lower risk investments are much more worthy of consideration in today’s market. For example, we have been able to shift assets from more volatile “bond-replacement” investments such as real estate, hedge funds and dividend stocks, and back into traditional bonds.

We welcome this return to more typical levels of interest rates and a more rational cost of capital, which should benefit bottom-up fundamental investors that focus on quality, cash flow and other factors that were de-emphasized in the era of “free” money.

While the risk of recession in 2024 appears to be falling, it is far from gone, and our expectations for equity returns going forward are still muted—simply because the strong equity returns of 2023 were largely the result of expanding multiples rather than earnings growth. We have modestly reduced our equity allocations, trimming most notably from the richly valued U.S. large-cap growth segment.

EQUITIES

With higher interest rates, cash flows and leverage become larger drivers of performance for equities, and this is especially true in a highly concentrated market being carried by a high-flying subset of stocks.

Valuations in the U.S. are broadly “elevated,” but there is a clear dichotomy, with the Magnificent Seven stocks trading at nearly 50x earnings at the end of 2023, while the rest of the U.S. large-cap market traded at a more down-to-earth 18x multiple.

When looking at smaller companies in the U.S., valuations appear lower than their long-term averages. Valuations in Europe and Asia are also more attractive. This valuation backdrop is informing several of our equity allocation stances.

Overweight U.S. small-cap: We typically maintain an overweight to smaller companies, which generally outperform larger company stocks over time, and which often fly under the radar of Wall Street research coverage. The recent underperformance of small-caps has made this segment even more attractive due to relative valuation. If the U.S. does avoid a recession, we would expect this allocation to meaningfully outperform the broader market.

Modest tilt to value within equities: We have had this “tilt” in place for a year or more; given the relative underperformance of value stocks in 2023, this valuation gap has only widened and value stocks therefore remain attractive to us. We would expect value stocks to be buoyed if the U.S. economy stays strong in 2024.

Infrastructure and energy transition: We still see value in allocating to infrastructure. These are high-quality, long-life assets that provide mission-critical products and services with monopoly-like characteristics. These assets facilitate the movement and storage of energy, water, freight, passengers and data. Even if inflation continues to cool, it remains well above long-term averages, and we appreciate the consistent inflation-linked cash flows of many infrastructure companies. Furthermore, the “non-deferrable” demand for these assets helps protect revenues in periods of economic weakness. We also see meaningful opportunities for capital investment through a greater demand for assets that transmit and store data, renewables in the quest for decarbonization as well as the reshoring of physical assets largely described as deglobalization. Finally, valuations have also come down materially, presenting an attractive entry point for allocations here.

Globally-oriented European exposure: Though economic risks are certainly present, our managers are finding selective opportunities to invest in leading global companies that are trading at discounted valuations because of their European domicile. Europe is home to preeminent names in aerospace, finance, consumer staples and luxury brands; thanks to inflation, sluggish European growth and the ripple effects of the Ukraine war, many of these names have underperformed the broader market—despite generating much of their revenues from outside Europe.

“Pan-Asian” exposure with reduced weighting in China: Chinese stocks disappointed investors in 2023; the reopening of the Chinese economy did not spur growth as many had hoped. China’s massive real estate sector is burdened by declining home sales, falling prices and the bankruptcy of some of the country’s largest real estate developers. Political and regulatory uncertainty also remains high, increasing the risk of investments in China.

Meanwhile, growth has remained strong in India, and Japan has made major progress in terms of both profitability and better governance. On the margin, we’ve been shifting capital out of China to more pan-Asian strategies, and we’ve seen many of our Asia managers de-emphasize China as well. In our view, the market clearly still represents massive potential, and we will continue seeking out ways to capture its opportunities without exposing ourselves to undue political and economic risk.

FIXED INCOME

After years of meaningful underweights, most of our client portfolios are now at or above our long-term targets for bonds, and portfolio durations have been extended (despite still being relatively short compared to fixed-income benchmarks). We are unlikely to match the duration of the bond market, which has extended materially in recent years as companies locked in lower yields with longer-maturity bonds.

At or above target weight to fixed income: We have funded our “re-allocation” to bonds from areas like real estate, hedge funds and dividend stocks (in “lean” years when bonds offered paltry returns, these higher-risk areas helped provide the yield and diversification that bonds traditionally offer).

Gradual extension of duration: Our latest increases in duration occurred as the 10-year Treasury yield approached 5%; after subtracting long-term inflation expectations of 2%, the 10-year presented an attractive real yield of nearly 3%, which is the highest we’ve seen in 20 years. While there is certainly a scenario in which rates move higher again, we believe the current yield on our bond portfolios should provide ample protection against that.

Selected opportunities in credit: In 2023, credit markets repeatedly offered us equity-like returns with lower risk. Whether one compares bonds vs. stocks, private credit vs. private equity, or real estate debt vs. real estate equity, we are broadly seeing better risk-adjusted returns from certain credit investments than from equity counterparts; importantly, we find that solid, bottom-up credit research is an essential step in unearthing and vetting these opportunities.

PRIVATE INVESTMENTS

Public markets are reaching all-time highs, but private markets are lagging in this new regime of higher interest rates. There is always a delay in how private investments respond to market conditions, but the lag has been especially pronounced in this cycle. Fundraising and deal activity levels are near the lows reached in 2009, despite a strong economy and healthy public markets.

While we don’t think this “reset” stage is quite finished, we do believe we’re setting up for what will eventually be a strong period of private market returns. Market timing in private markets is nearly impossible, and we believe that consistency with one’s commitments is the key to long-term success. We are favoring credit commitments over equity, and have slowed down in real estate, but we are not skipping vintages from our most important manager relationships. As deal activity has slowed, we are feeling more confident that these managers will be able to pace their investments over a longer multiyear period in keeping with historical norms. When clients commit to these funds today, they are committing to investments that may occur five years from now—perhaps at more compelling prices.

Venture capital: As the cost of capital has risen and investors are hyper-focused on cash flow and path to profitability, venture funding has dried up and valuations have come down. We expect 2024 to be a crucial year in venture capital; companies that raised large war chests in the past will need to raise more money, and deals may occur at more attractive valuations as a result. More venture-backed companies are likely to fail this year, as investors will be more reluctant to continue funding companies with weaker business models or operations. Additionally, we expect a moderate shakeout in the sector as some venture firms close and non-traditional participants (e.g., mutual funds and hedge funds) retreat. The ongoing retrenchment is likely to lead to a healthier and more attractive investment environment for our clients, and we are glad for opportunities to re-up with our highest-conviction managers when they come to market, especially with regard to earlier-stage venture managers.

Lower middle market: We tend to favor lower middle market strategies in private equity—typically these are smaller managers who write smaller checks and generally use less leverage to generate returns. This approach makes even more sense in the current environment, where leverage is much more expensive. A number of our managers specialize in adding value operationally, and many of them have expertise in turnarounds that may be quite helpful in a more challenging environment for levered businesses.

Private credit/income: Returns in private credit are likely to be buoyed by higher interest rates in the coming years. Most of these are floating-rate loans, benchmarked to overnight lending rates of 5.0%. With banks pulling back from lending in the wake of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, lenders have more bargaining power these days and terms have also improved.

We acknowledge that the private credit space has experienced enormous AUM growth in recent years, but we believe that potential returns in this space could exceed 12%, which compensates us, in our view, for the risk that perhaps too much capital is chasing these opportunities.

Real estate: This sector has been very quiet as the big move in interest rates has severely curtailed deal activity. When deals are being done, some are driven by distress, such as a need to refinance or to inject required capital into a property. While we continue to back our longest-standing relationships in this space and will not be skipping vintages, we have downsized our commitments to real estate equity, to make room for compelling opportunities in real estate debt. Much like with private credit, we are simply seeing more opportunities to generate equity-like returns in real estate debt, presenting a more attractive risk-adjusted return compared to real estate equity.

HEDGE FUNDS

Are hedge funds back? Returns were disappointing for many years after the 2008-09 credit crisis, but perhaps the sector has turned a corner. Ever since the “meme stock” craze of 2021, where managers suffered mightily shorting stocks like GameStop, industry performance has been quite strong.

Higher interest rates have led to two big benefits for hedge fund investors: 1) yields exceeding 5% on the cash they receive when the fund shorts stocks and 2) the return of short selling as a fruitful endeavor, thanks to the end of the “free money” era and a decline in individual stock correlations as a result. The year 2023 may go down as our best year in this space since 2007, in both absolute and relative terms.

Despite all of this, we need to temper optimism for the sector with prudence in our asset allocation thinking. For a number of clients, reducing hedge fund exposure makes more sense now that they can earn 5% on short-term deposits.

Smaller, nimbler equity long-short managers: This represents a growing percentage of our allocation in recent years. Fund size tends to be the enemy of performance when shorting stocks, as many of the best shorting opportunities are in small-cap or mid-cap companies. The vast majority of our long/short equity managers today are running strategies with <$5 billion in assets, giving them the flexibility to short these smaller companies.

Diversifying exposure to healthcare/biotech specialists: We launched a dedicated life sciences fund portfolio in 2022, the Brown Advisory Biotechnology Partners Fund; the idea may have been early, but we don’t think it was wrong and we added it to our allocations in 2023. We think good stock-pickers can thrive in this space, as most investors shy away from investing in companies that require specific scientific knowledge and bear the risk of drug approvals. This is precisely why we like the sector: the dearth of informed investor competition. This sector today remains relatively inexpensive by historical standards, and large-cap pharma companies remain flush with cash for acquisitions, which are increasing in number and size.

Long/short credit, distressed and multi-strategy managers: We expect long/short credit managers may see more opportunities as levered companies struggle with higher costs of capital. We’ve seen excellent results from these managers in recent years and a new distressed cycle could further enhance their opportunity set.

Multi-managers: Over time, we have limited investment in multi-manager hedge funds (multiple portfolio managers running their own portfolios, typically with tight risk management and a market-neutral stance) due to high fees and low transparency, for the most part. In recent years, however, a new group of these funds started to offer more palatable fees and much better transparency. When managed well, the results of these multi-manager funds can really help portfolios with their low volatility and low correlation to core asset classes. We believe they were, in many ways, the best replacement for bonds during the long, low-rate environment of the past few decades. While we may have less of a need for these strategies thanks to higher interest rates, we do think these funds can play an important role.

Note: All commentary sourced from Brown Advisory as of 12/31/23 unless otherwise noted. Alternative Investments may be available for Qualified Purchasers or Accredited Investors only. Click here for important disclosures, and for a complete list of terms and definitions.

2024 Asset Allocation Perspectives / Outlook

INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE

HIGHLIGHTS

Despite fears of a macro-driven correction due to rising rates and inflation, markets showed surprising resilience last year.

We are monitoring several risks at the start of 2024, from weakening consumer balance sheets to the pending 2024 U.S. elections. Despite these medium-term pressures, we remain optimistic about long-term prospects for growth, especially given the transformative potential of innovations within AI and with GLP-1 treatments.

The story of financial markets in 2023 can be summed up in two words: surprising resilience.

Stubborn inflation, alongside the most pronounced interest rate hikes of the past 40 years, led many to expect a U.S. recession in 2023. As the year progressed, we witnessed large U.S. bank failures, repeated threats of U.S. government shutdowns, the disappointing re-opening of China’s economy, continued war in Ukraine and war in the Middle East.

If you had given us this script in advance, we would not have predicted a favorable outcome for markets, much less a 26%+ return for the S&P 500® Index!

There are several reasons why these results were a positive surprise: excess savings from the pandemic being unleashed, elevated deficit spending from governments, excitement about artificial intelligence and the continued growth of cloud computing. The “AI craze” specifically favored seven massive technology companies (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Tesla and NVIDIA) that have dominated the U.S. market for years. These “Magnificent Seven” companies rose by 107.0%, while the rest of the S&P 500® Index rose by only 12.5%, making 2023 the narrowest market in decades.

Additionally, inflation finally saw meaningful deceleration in the latter part of the year, with core inflation falling within reach of central bank target levels in both Europe and the U.S. by year’s end. This also helped give markets confidence that a quick pivot by central banks to lowering rates could generate a soft economic landing (i.e., bring inflation down without a recession). However, it is important to remember that despite the drop in bond yields during the fourth quarter, interest rates were still higher across the curve in 2023 (even following the historic increase in rates during 2022). Therefore, it is far too soon to say how the recent slew of rate hikes will impact the economy in 2024 and beyond. Decades ago, Milton Friedman helped us understand that the Fed’s interest rate decisions are not tweaks with immediate results; instead, their effects have “long and variable lags,” and it can take years to fully see these effects filter into markets, especially into other debt markets (source: “A Program for Monetary Stability,” by Milton Friedman).

These lags may be even longer than usual during this cycle. U.S. consumers took advantage of what were low mortgage rates—mortgages make up 70% of the typical U.S. household’s debt, and four out of five U.S. 30-year mortgages are at or below 5%. These homeowners’ mortgage costs are likely lower than the interest they earn from most savings accounts; they are well shielded from the economic pain of higher rates. Similarly, corporations took advantage of the prior decade’s low rates, extending the average duration of corporate debt from six years to nine years between 2012 and 2022. Thus, corporations and U.S. consumers both had some built-in padding that protected them from higher debt costs in 2023.

The situation in Europe is more complicated, however. Mortgage markets differ by country but suffice it to say that in most European countries, mortgages tend to be much shorter in duration. In the UK, for example, the majority of fixed-rate mortgages have a duration of between two and five years, after which they begin to rise and fall with interest rates. In Germany, things look a bit better with a growing proportion of borrowers recently opting for fixed-interest periods greater than 10 years, but there are still many pockets of Europe with meaningful exposure to variable-rate payments. The full impact of higher rates on the European consumer is arguably yet to be felt, so we remain cautious on the outlook, especially given European economies remain susceptible to the prospect of higher energy prices should the continent fail to be blessed with another mild winter.

Globally, barring a quick reversal in interest rates, those interest costs will likely increase over time. People need to sell homes, companies need new debt financing, and all of that will likely be more expensive going forward. Mortgage rates in the U.S. are near 7% at the time of this writing and briefly exceeded 8% during Q4 2023; 10-year U.S. Treasury yields had hit 20-year highs, while credit card APRs were at or near 30-year highs. Economic conditions in Europe are just as tight, if not tighter, given a higher reliance on bank credit, less fiscal support, a greater dependence on energy imports and an economy more exposed to global trade.

It is only a matter of time before these effects are felt in a more material way. Consumers are saving less today—and using more of their income to service their debts—than they have in 15 years (see chart below). Credit card and auto loan delinquency has started to rise, reaching pre-pandemic levels. Companies are starting to mention the impact of higher rates on consumer demand. All of this is starting to show up in reduced forward earnings guidance for some companies.

Paid to Wait

The looming impact of higher interest rates is one justification for caution as we look forward. Another, more positive reason, is that for the first time in more than a decade, investors are being paid well in defensive assets like cash and bonds. Real interest rates (i.e., nominal rates minus inflation) stand at multi-decade highs; meanwhile, stock market valuations are still elevated, especially after the Fed pivot-driven rally in November and December, which dampens their future return outlook from here.

The combined effect of these two trends is that bonds and cash simply “compete” much more effectively with stocks now than they have in a very long time. The “equity risk premium” (i.e., the estimated. incremental return from stocks vs. bonds) is currently at its lowest level in nearly 20 years—in other words, expected bond returns have nearly “caught up” with stocks (see table at right). Historically, stock returns have nearly doubled those of bonds (and for the past decade, absolutely trounced them), but today, expected returns are neck and neck.

THE "NEW ABNORMAL"

Historically, stocks and bonds have both offered desirable, risk-adjusted returns, with stocks offering a greater return. Over the past decade or so, this “truism” became untrue, as bond returns plummeted to less than 2%. However, with higher interest rates, we anticipate bonds will likely produce a more competitive return compared to equities going forward.

Source: Bloomberg, Brown Advisory analysis as of 12/31/2023.

Specifically, even when considering the recent drop in interest rates, longer-term rates (e.g., 10- and 30-year bonds) now allow investors to lock in positive real yields for many years into the future. This has given us confidence to extend the duration of our bond portfolios, which offers us some protection if economic growth slows further from here.

Despite the delayed impacts of central bank rate hikes, there are already winners and losers in an environment in which rates may stay “higher for longer.” Companies with too much debt, particularly the floating-rate variety, are struggling, as are unprofitable companies that need more capital and whose earnings are not expected to materialize in the near term. As quality-oriented investors (see: “High Quality Stocks for the Long Run?”), we prefer investments with lower debt levels and healthy free cash flow generation, and we believe that this preference should serve us well—especially during a period when access to low-cost capital will likely be quite limited. We are beginning to see opportunities in more distressed areas of the market but are moving slowly given the environment.

Increased debt costs may be a drag on shareholders and asset owners, but they are conversely a potential boon to lenders. The pullback in bank lending after the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, the pressure on companies with high levels of floating-rate debt, and the necessary recapitalization of many real estate properties have provided ample opportunities with attractive risk/reward. There are real problem loans from commercial real estate properties that sit on bank balance sheets today, and the severity of potential losses is just beginning to appear. We have seen a few office properties across the country sold at 50%–75% discounts to where they traded just a few years ago, and that is leading to not only a wipeout of equity holders, but also losses for lenders. The good news is that most of the largest banks have quite limited exposure to such loans and are well capitalized, with tightened oversight from regulators since 2008. We view the broader financial system today as sound. Many smaller regional or community banks in the U.S., that have far greater office loan exposure as a percentage of their assets, are struggling; they have slowed their pace of lending and may be forced to sell loans or assets at steep discounts. We have shifted more of our investments toward credit investments this year as a result of this dynamic and are continually evaluating new opportunistic distressed investment strategies focused on real estate.

Beyond the Magnificent Seven

Looking forward, another “trend” we are watching is more accurately described as an “anti-trend.” The stellar performance of the “Magnificent Seven” tech giants in recent years has resulted in large swaths of the broader stock market being heavily undervalued on a relative (and in some cases absolute) basis. We haven’t seen this level of market concentration since the 1970s. Those seven stocks drove 70% of the market’s return in 2023, and as of the time of this writing they trade at an aggregate valuation of more than double that of the rest of the S&P 500® Index. We still think several of these companies represent excellent long-term investments, but this concentration within major indices (to which so much capital is implicitly or explicitly tied) creates significant risks particularly given the thematic similarities within these companies. For all these reasons, we continue to shift capital on the margin to smaller companies and to non-U.S. opportunities in search of more attractive valuations.

Europe: Despite the challenges outlined above, our managers are broadly seeing more opportunities emerge in European-listed companies, as negative sentiment on the continent as a whole has disproportionately weighed on the share prices of a select group of business models. Companies like the London Stock Exchange Group have been treated as European market-sensitive cyclicals, but in reality, they are market-leading firms with diversified, global businesses and strong secular growth drivers. Global aerospace leaders Safran and Airbus reside in Europe; we believe that their high return on invested capital positions them very well, even before considering the benefit of any potential cyclical rebound from the pandemic, or from secular growth in travel. Broadly, valuations are cheaper in Europe than the U.S. and we are optimistic that bottom-up research can continue to unearth attractive investments there.

Asia: We had a number of our research team members travel to Asia this year, in hope of gaining insight into China’s recovery falling short of expectations, as well as Japan’s markets surprising many with their renewed vigor. We remain convinced that China still merits investor attention, with a plethora of quality growth companies, market inefficiency that rewards solid fundamental research and low valuation relative to its own history. However, these positives are being overshadowed by the growing uncertainty of the government’s ongoing support of free markets, China’s looming real estate debt woes, and the country’s highly challenging demographics. The demographic situation is more dire than many realize; China’s birth rate has dropped by 40% since the start of the pandemic, and recent estimates suggest its working-age population may decline by 20% in the next 20 years—a potentially MASSIVE drop in overall production (equivalent to ~40 million workers leaving the U.S. workforce over a similar timeframe). Meanwhile, Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power and the Party’s various steps to retreat from market-oriented capitalism have undermined business and investor confidence and pushed foreign direct investment into negative territory for the first time on record (see chart below).

At this point, we favor a pan-Asian approach to our allocations in the region. We are focusing more research on Japan, where inflation has been a welcome change after decades being mired in deflation. Japan’s wage growth and retail sales trends are each at 30-year peaks. Renewed regulatory pressures aimed at profitability and governance also present an opportunity for both margins and valuations to improve in Japan—something that can’t be said of many markets in the world.

Private Markets Stalemate

Private market deal volumes are at their lowest point in years, and valuations for these deals are in a state of flux despite solid fundamental performance from many underlying private companies in our buyout portfolios and properties in our real estate portfolios. Growth has certainly slowed in our venture portfolios, but many of our venture-backed companies have tightened their belts, reduced their cash burn and are charting a path toward profitability. Still, losses are very likely to materialize in many venture portfolios as this segment of the market continues through its natural cycle.

Deal pricing remains a challenge, and at times valuation debates can lead to a stalemate when buyers and sellers are unwilling to acknowledge shifts in market realities. Higher financing costs typically lead to lower cash flows, and higher interest rates typically lead to lower multiples paid on those cash flows. Can buyers and sellers agree on these projections, and on what they imply for valuation? And can a buyer get financing for their purchase at rates that make the valuation work? The continued concerns over an economic slowdown have also served to dampen this market.

Private valuations and marks have fallen steadily coming out of the pandemic and are now more in line with public comparables. They very well may have further to fall. That said, we believe deal activity may increase in the near future, as the reality of higher rates sets in and the need for capital forces sellers to the table with more reasonable expectations. In general, we would expect to see higher capital call activity this year, and a continuation of a lean period for distributions in private investment portfolios.

We have favored allocations to debt over equity for many of our commitments in 2023. Earlier, we mentioned the more favorable comparison between debt and equity in public markets, and that is happening in private markets as well. Investors are being offered excellent returns for private credit risk at the moment. In the equity commitments we have made, we have favored cash-flow-producing investments, given the continued uncertainty with respect to both the economy and the valuation environment.

Regardless of the sector, we remain highly aligned with our top managers, and are broadly resisting the instinct to indiscriminately cut back on allocations. Private equity deal activity slowed yet again in 2023, with most investors pulling back. Investors have been rewarded over time for leaning in during periods like this, especially with managers that have demonstrated their skill across full market cycles. Of course, all private investments need to be weighed against each investor’s risk profile and circumstances, particularly in tougher market conditions.

Buckle Up for a Big Election Year

Some 40 countries, representing nearly half of the world’s population and GDP, will have national elections in 2024. Historically, elections have not had extreme impacts on markets, and we would find it difficult to draw conclusions about market performance even if we could predict the outcome of the election, which of course we cannot. (We do acknowledge that the upcoming U.S. presidential election has the potential to drive greater volatility than most).

Over the past century, S&P 500® Index returns in election years were, on average, slightly higher than in non-election years. Returns historically were better when a Republican won, as shown in the chart below. However, election years may also be accompanied by financial crises, global wars and/or a wide variety of economic scenarios, which often overwhelm political results.

For example, in the chart below, we summarize average results over the past century, and then offer the same summary excluding the outlier results of 2008. You will see that without the market results from the 2008-09 credit crisis, the data now “suggests” that election years offer notably higher returns, and the results are equal when Democrats and Republicans win. Further, we can see that “expected” sector returns under Republicans and Democrats do not always fit expectations (see chart on page 10); for example, a “political investor” likely would have chosen to invest in the energy sector under Trump and not under Biden, which would have led them to a weaker return. We believe that it would be foolhardy to draw investment conclusions about election years using the very noisy historical data available to us.

The U.S. stock market fared well under both Trump and Biden, but it would be impossible to assign credit to either administration for positive returns in recent years. Trump’s tax cuts likely helped, as has Biden’s infrastructure spending; however, one could argue that consistent 7% fiscal deficits under both administrations, 0% interest rates up until very recently, and massive technology disruption have all been bigger factors. As is often the case, we may want to give less credit to “the economy” and more credit to the fundamental successes of well-run companies like Microsoft, Amazon and the other tech titans that have propelled investor fortunes through the past two presidential terms.

All that being said, this election does stand out. Both Biden and Trump would be the oldest person ever sworn in as president, so questions regarding their health complicate matters. Meaningful legal troubles add yet another dimension of uncertainty to the equation. Further, we fear another election when the validity of the process is challenged, especially at a time when trust in government is at an all-time low (just 16% of Americans trust the government to do what is right, down from ~60% two decades ago). Third-party candidates may create more volatility than normal, in a year when the likely nominees from major parties both have track records as sitting presidents. While any one of these scenarios could rattle markets, they are unlikely to materially shift our assessment of individual investments, and we would seek to capitalize on buying opportunities that may emerge from any volatility.

As for potential changes in policy, either administration would be faced with the expiration of Tax Cut and Jobs Act provisions, which would mean higher marginal income tax rates and a halving of the estate tax exemption. Today’s lower corporate and capital gains tax rates are not set to expire, but they may become political issues given higher interest rates and heavy ongoing deficit spending. Biden’s 2024 budget proposal suggests increases to taxes, while Trump has suggested lowering corporate taxes further—in other words, both candidates are consistently representing their parties’ traditional tax views. However, a dysfunctional Congress may prove to be an immovable obstacle to either party’s plans.

End of the Free Money Era: The Bright Side

For us, investing does not involve “placing bets” that require a singular market or economic outcome to pay off. Instead, we prefer to mitigate risk by spreading it out: We examine multiple possible “bull” and “bear” scenarios, estimate the probability of those scenarios as best we can and prepare our portfolios to perform well in as many likely scenarios as possible.

In looking at these various potential scenarios for 2024, we see an elevated probability of recession in both the U.S. and Europe. Inflation, despite a large and welcome decline in late 2023, still remains above the comfort zone for central bankers on both sides of the Atlantic. There is a high likelihood that both inflation and interest rates may remain high relative to the past decade. There is also a risk that war in the Middle East or Eastern Europe spreads, straining global energy supplies and potentially sparking renewed inflation.

At the same time, governments in the developed world are facing a growing issue with debt and deficit spending: Levels that were largely sustainable with low interest rates are increasingly unsustainable now that rates have risen so notably. Addressing the overarching situation may require a combination of increased taxes, lower government spending and/or cuts to entitlements (more on that later). The debt ceiling debate in the U.S. has shed some light on this issue, but it still appears underappreciated by most investors, in our view.

This collection of market risks confronts stock valuations that are above their long-term averages (particularly for U.S. large-cap stocks) and well above where they typically sit when interest rates are at these levels.

With all of this in mind, we remain committed to our portfolio investments in quality public companies; long-term compound growth from public equities is the primary driver of wealth creation for most of our clients, and we expect that to remain true in the future despite current market challenges. However, we are tilting portfolios toward the opportunities we see in fixed income and credit and shifting some capital away from the “Magnificent Seven” and other market segments with lofty valuations, to spots where valuations appear more attractive.

As we mourn the end of the free-money era (2023 saw the first positive real interest rates from the Fed in more than 13 years), we should also celebrate that ending. In a healthy market, there should be a cost of capital—it should not be free to everyone, and now that it isn’t, we believe it will be a good thing in the long term for both fundamental investors and the economy alike. Going forward, cash-burning companies with flawed business models will likely consume far less productive capital than they did during this era. Investors are once again being rewarded for their focus on cash flows, rather than simply riding on the tail of an exciting narrative about the latest unproven market. The pendulum has swung back in favor of the providers of capital (investors) relative to the consumers of capital (companies, properties, etc.), and this should reward thoughtful, active investing.

The new interest-rate reality also lets us return to more balanced portfolio construction. No longer does one need to heavily allocate to risky assets to reach attractive return targets. We think constantly about the individual goals of each portfolio—who is the client, what are the funds for, when are the funds needed, etc.—and tailor allocations accordingly. For pools of capital with shorter time horizons, such as a foundation that is spending down its assets, or an individual nearing retirement, it is far more attractive today vs. 10 years ago for such clients to shift toward fixed income opportunities.

Despite higher rates and our somewhat cautious outlook, we remain open to the potential positive scenario of a soft landing in the U.S.—one in which inflation falls further, the Fed cuts rates meaningfully and parts of the industrial economy rebound to offset consumer weakness. If this past year has reminded us of anything, it is that predicting both economic and market outcomes is a challenging endeavor. To put it more bluntly, everyone in the investment business tries to anticipate where markets are headed next, and the best of us get it wrong nearly half the time. The vast majority of finance professionals greatly underestimated the strength of the U.S. economy in 2023, and it wouldn’t shock us if the same occurred in 2024.

While economic prognostication is nearly impossible, it is far more possible to make reasonable projections about companies and industries. We find it most useful to orient our thinking around the intrinsic value of individual investments, and then shift portfolio weightings based on those observations. When assets appear cheap to our estimate of value, we shift capital in that direction. What strikes us today is the disparity between the valuations of various companies based on their fundamentals, as well as disparities between small- and large-cap companies, and between international and U.S. markets—in each of these cases, there is healthy fundamental and valuation evidence leading us to lean in specific directions. This is a welcome development after years in which macroeconomic stresses continually swamped the market’s ability to separate the good from the bad. We hope these new realities will buoy our efforts to outperform our client’s blended benchmarks over the long term.

Note: All commentary sourced from Brown Advisory as of 12/31/23 unless otherwise noted. Alternative Investments may be available for Qualified Purchasers or Accredited Investors only. Click here for important disclosures, and for a complete list of terms and definitions.