Thomas Hobbes, the 17th century English philosopher, famously argued in his book “Leviathan” that without government, life would be “…poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Considering this in the context of economic cycles, the progressive evolution of governmental intervention through fiscal and monetary policies has broadly ameliorated conditions of “life” for participants in the global economy since the mid-20th century. Now, as we appear to be emerging from the post-pandemic adjustment within global economies – particularly in developed markets – it occurs to us that we may be nearing another, rather large, inflection point in the global macroeconomic landscape. We believe we are finally exiting the economic and market structure that has existed since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) – what economists and investors have become conditioned to believe would be the “new normal” – and are transitioning back to an “old normal,” reminiscent of the pre-2007 world.

A Brief History of Economic Cycles

Looking at U.S. economic history through the lens of Hobbes’s statement, we observe increasingly elongated business cycles, with shorter periods spent in recession. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, in the 75 years before 1946, there were 18 business cycles with an average peak-topeak length of 50 months, or 4.2 years, including events such as the Industrial Revolution, the Great Depression, and two world wars, which shaped the global economic landscape profoundly.

In the 75 years from 1946 through 2020, there have been 12 business cycles that averaged 75 months, or 6.3 years. This latter period saw major economic developments such as the post-war boom, the Tech Revolution, the GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic, each with distinct economic implications. During this period of history, many factors, including globalisation, demographics and excess savings created a significant disinflationary environment. This led to a multi-decade decline in developed world interest rates, ultimately reaching levels that went below zero in several economies. This economic landscape provided more room for governments to be increasingly active in their interventionist policies, both orthodox in nature, and unorthodox. We believe this backdrop has also been a significant tailwind to increasing aggregate global growth, driven particularly by those emerging economies that were the biggest beneficiaries of outsourced production. What we find particularly notable is that recessions from 1871 through 1945 lasted an average of 21 months, but from 1946 through 2020, the average recession duration more than halved to 10 months.1 Hence, the Hobbesian belief in the importance of the government in mitigating, in an economic sense, those “nasty and brutish” periods of financial hardship for its citizens seems borne out.

Inflection Points

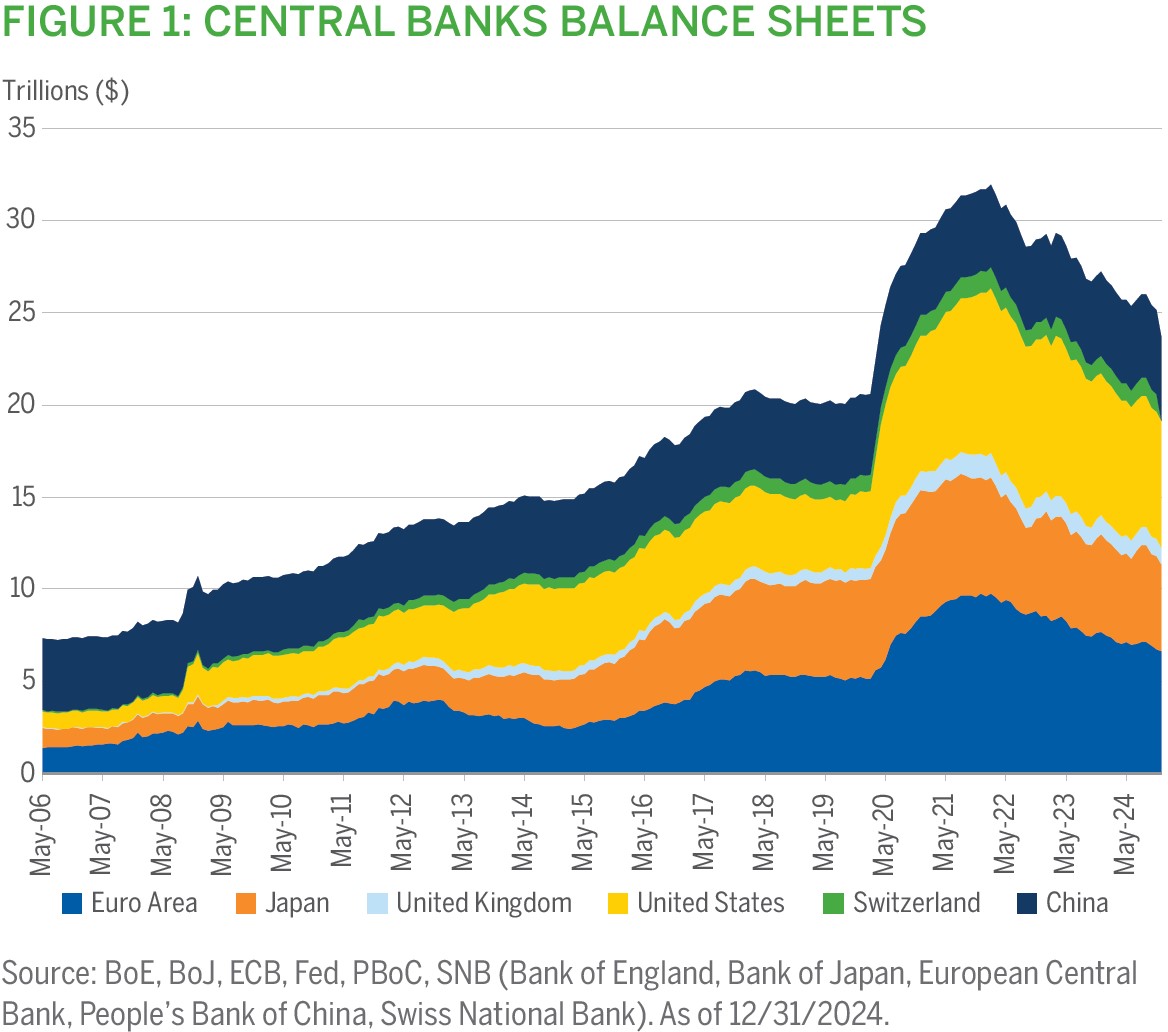

However, we would argue that these positive tailwinds have been abating in recent years, and have had negative secondary implications. On the heels of the GFC, global central banks began providing massive amounts of liquidity to the financial system via quantitative easing policies that accelerated even further during the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 1 shows the magnitude of these policies across several major economies in terms of central bank balance sheet quantum. This era of “abundance,” when thinking about interest rate management and liquidity within the financial system, brought with it a new paradigm within developed market interest rates, namely zero interest rate policies (ZIRP). Given the fact that interest rates are effectively the price of money – particularly real interest rates – the cost of risk during this period fell to unprecedentedly low levels and allowed for higher risk-taking activities within financial markets such as debt-fuelled investment and an increasing appetite for credit risk.

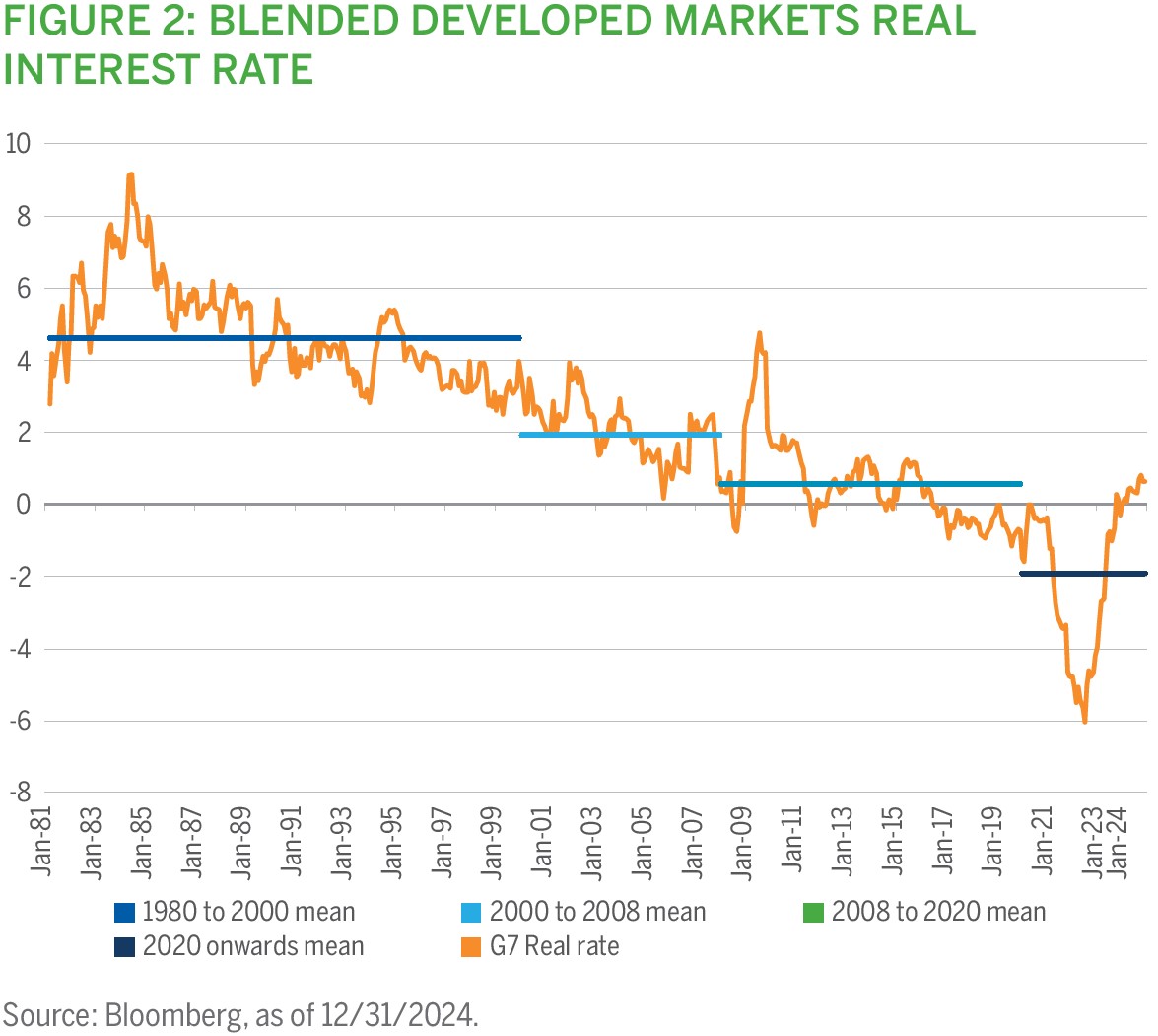

Moral hazard has oftentimes entered the discussion when thinking about governmental involvement within markets during this era. We think it is important to consider real interest rates in this context. When looking across developed market economies, real interest rates have had several discrete regimes with rangebound real rates, each of which has moved sequentially lower to reach levels well below zero in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Only recently, we have seen a meaningful repricing of these interest rates, as seen in Figure 2.

A natural extension of this real interest rate paradigm is growth in the wealth gap – the power of capital coming at the expense of labour. Wealth gaps beget nationalist and populist politics that drive protectionist economic policies, which can ultimately reverse global economic foundations that have been built, such as supply chains.

This comes at a particularly sensitive time given the stagnating nature of globalisation, defined by exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, as seen in Figure 3. Beyond the more recent challenges associated with politics, demographics are undergoing their own sets of transitions. Many of the economies that have enabled and/or benefitted from global market integration had growing and young populations that were migrating to urban centres. More recently, these trends are peaking, and in some cases reversing course as populations begin to age, and in some cases shrink, creating additional challenges to globalisation. In other words, we would argue that the growth and disinflationary impulses associated with globalisation are increasingly at risk given the demographic and political tailwinds, which are transitioning to headwinds.

The current inflationary trends that now exist across global economies make it far more difficult for central banks and governments to maintain the loose monetary and fiscal policies that were a staple of the post Global Financial Crisis (GFC) era. Factors including fractured supply chains, increasing power to labour at the expense of capital, nationalistic policies such as trade tariffs and exorbitant governmental spending – including the investments required to address climate change – reinforce inflationary pressure over the medium-to-long term. Also constraining policymakers and management teams has been the extensive use of debt for public- and private-sector investments that are likely to be more costly to support with higher interest rates as balance sheets have grown in size, such as those seen for the governments in Figure 4. This could change the way investors think about risk, which could have meaningful implications on the shape of global credit and sovereign curves – particularly for longer-end maturities.

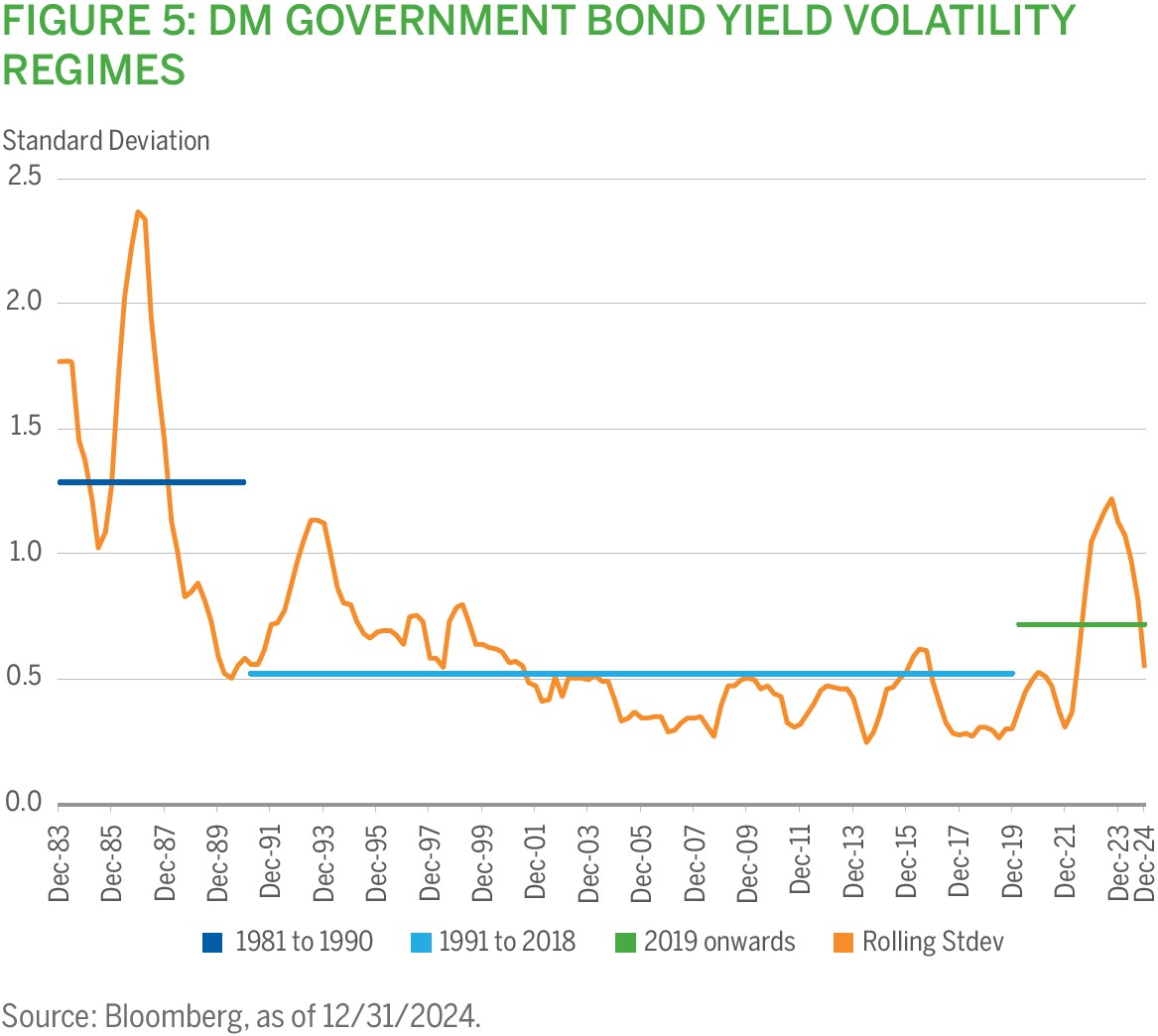

If we accept the “new normal” characterisation of the post-GFC era up to the COVID-19 pandemic and acknowledge the inflection points indicating a new investment regime that resembles the pre-GFC era – when there was a cost for risk and business cycles were more meaningful – then perhaps “old normal” is an apt description for this emerging paradigm. We might see this reflected in higher volatility for developed market interest rates, as seen in Figure 5.

In the U.S. speculative credit space, pre-GFC default cycles had higher peak and average default rates versus the post-GFC era (Figure 6). A return to the “old normal” could lead to increased peak and average default rates. If average default rates rise from 3.6% back to 5.4% (Figure 6), this could translate to an approximate 100 basis point increase in credit spread on the Bloomberg U.S. Corporate High Yield Index, assuming other factors remain constant.2

In this new (“old normal”) market paradigm, the disinflationary tailwinds that prevailed up to this point, which enabled government intervention in markets, will likely be difficult to replicate. The massive quantum of debt accumulated on public and private balance sheets will have to be reconciled with higher interest rates, and investors will have to contend with some degree of cost for risk when assessing future investments. With these considerations in mind, we may indeed be moving toward a future that more closely resembles Hobbes’s grim outlook of the world, with the added challenge of limited government intervention. Nonetheless, this is not necessarily bad for financial markets, as it signals a return to economic orthodoxy where poorly performing companies fail, valuations reflect the actual risks that investors must bear, and volatility exists and matters, potentially leading to shorter, more turbulent economic cycles with longer recessionary periods where the ability of governments and central banks to buffer against economic downturns may be significantly diminished. We believe this would be an environment where fundamental and sustainable investment principles return to the forefront, as they were in the days before the GFC.

The Opportunity

All this talk of inflection points is important to us because they are fundamental to building and maintaining conviction within our investment decision-making that spans macro-oriented factors, which are primary drivers to fixed income investment performance, including duration, curve, and asset allocation positioning, and micro-related factors such as security selection. Our investment process hinges on a dynamic asset allocation approach with awareness of the economic cycle coupled with risk-adjusted return objectives informed by bottom-up, fundamental, sustainable investment research. We believe the abovementioned inflection point that today’s global economy and fixed income markets are experiencing creates significant investment opportunities for our approach to portfolio management.

So how do we think about managing portfolios? The first step is to recognise that economic cycles have multiple phases and that each phase of an economic cycle requires a different level of portfolio risk, as well as composition of risk (Figure 7). Top-down factors are typically the dominant driver of fixed income risk and returns. Therefore, the assessment of where we are in an economic cycle that ultimately defines our portfolio construction is the single most important decision we must take. For example, in the recovery phase of an economic cycle –we can use the period right after the GFC when credit spreads were at their all-time wides and monetary and fiscal policy were at their easiest levels – we positioned portfolios at the upper levels of their risk limits, with most of that exposure coming from credit risk, to maximize risk-on opportunities when valuations compensate us appropriately and we have macro tailwinds behind us. Conversely, as the cycle migrates over its peak and into the slowdown phase – and that’s where we think we are today – we seek to run the lowest levels of portfolio risk, and the composition changes accordingly. A defensive market environment typically means significantly less credit risk and a larger share of the risk coming from interest rates.

This new economic reality calls for adaptation, resilience, and flexibility. Businesses, investors, and policymakers must prepare for a world where the economic landscape shifts more rapidly and with greater intensity. The investment strategies that worked over the last 15 years may no longer be sufficient as we navigate the uncharted waters ahead. Investors may be tasked with rethinking their approach to managing economic cycles and market dynamics, and it is our strong belief that taking a dynamic and flexible approach to managing portfolios, integrating both top-down and bottom-up research, will be critical to generating alpha and providing capital preservation for clients.

PORTFOLIO MANAGERS, GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE TOTAL RETURN BOND STRATEGY

Chris Diaz, CFA

Portfolio Manager

Ryan Myerberg

Portfolio Manager

Colby Stilson

Portfolio Manager

1 The World Economic Forum, 2024. 2 Other factors include dollar price, excess return, and recovery rate assumptions.

Disclosures

The views expressed are those of the author and Brown Advisory as of the date referenced and are subject to change at any time based on market or other conditions. These views are not intended to be and should not be relied upon as investment advice and are not intended to be a forecast of future events or a guarantee of future results.

Past performance may not be a reliable guide to future performance and investors may not get back the amount invested. All investments involve risk. The value of the investment and the income from it will vary. There is no guarantee that the initial investment will be returned.

All investments involve risk. The value of the investment and the income from it will vary. There is no guarantee that the initial investment will be returned.

The information provided in this material is not intended to be and should not be considered to be a recommendation or suggestion to engage in or refrain from a particular course of action or to make or hold a particular investment or pursue a particular investment strategy, including whether or not to buy, sell, or hold any of the securities or issuers mentioned. It should not be assumed that investments in such securities or issuers have been or will be profitable. References to specific securities or issuers are to illustrate views expressed in the commentary and do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold or recommended for advisory clients.

Sustainable investment considerations are one of multiple informational inputs into the investment process, alongside data on traditional financial factors, and so are not the sole driver of decision-making. Sustainable investment analysis may not be performed for every holding in the strategy. Sustainable investment considerations that are material will vary by investment style, sector/industry, market trends and client objectives. The strategy seeks to identify companies that it believes may be desirable based on our analysis of sustainable investment related risks and opportunities, but investors may differ in their views. As a result, the strategy may invest in companies that do not reflect the beliefs and values of any particular investor. The strategy may also invest in companies that would otherwise be excluded from other funds that focus on sustainable investment risks. Security selection will be impacted by the combined focus on sustainable investment research assessments and fundamental research assessments including the return forecasts. The strategy incorporates data from third parties in its research process but does not make investment decisions based on third-party data alone.

“Bloomberg®” is a service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates, including Bloomberg Index Services Limited (“BISL”), and has been licensed for use for certain purposes by Brown Advisory. Bloomberg is not affiliated with Brown Advisory and Bloomberg does not approve, endorse, review, or recommend the Global Sustainable Total Return Bond Strategy. Bloomberg does not guarantee the timeliness, accurateness, or completeness of any data or information relating to the Global Sustainable Total Return Bond Strategy.

Terms and Definitions:

Alpha is a measure of performance on a risk-adjusted basis. Alpha takes the volatility (price risk) of a portfolio and compares its risk-adjusted performance to a benchmark index.

Duration is a time measure of a bond’s interest-rate sensitivity, based on the weighted average of the time periods over which a bond’s cash flows accrue to the bondholder.

Volatility is the degree of variation of a trading price series over time, usually measured by the standard deviation of returns.